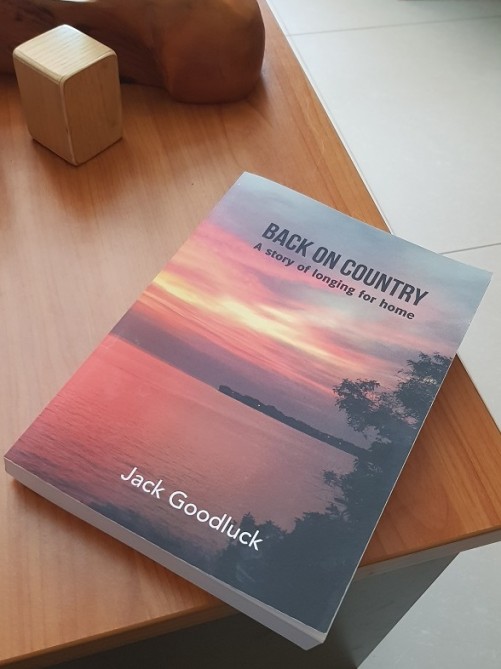

A compelling story with powerful characters set in the Northern Te rritory of Australia. Culminating on top of the sacred Gujigari Rock of the Wainanda clan … who will lose their nerve first?

rritory of Australia. Culminating on top of the sacred Gujigari Rock of the Wainanda clan … who will lose their nerve first?

The cast

Manggilulu : a young up and coming indigenous leader, too young to be catapulted into a position of intrigue, where his wit and passion clash with the white administrators.

Was he guilty of the murder that he was apprehended for?

Livvy : an anthropologist, who’s canny mind links the past to the future with telling accuracy.

George Simpson : long deceased but his legacy still pull the strings.

Gray Bridges : the Communication specialist who is caught between the authority of the government department he works for, and the respect for the First Nations People he serves.

Fred Archer : Director, Liaison Unit of indigenous affairs: an indigenous puppet of the administrators or a renegade in disguise?

Bilago : a drunk, who carries the secret that can unravel the past.

Edward Blyth : Chief Minister of the Northern Territory: Imperious in his belief of aboriginal management, and that “white is right.”

Arlene : beautiful, emotional, and fragmented from a life of racialism… Will she emerge triumphant or broken?

Jambagarila : a Wainanda Elder; a traditional who follows the guidance of the ancestors and ruthlessly disciplines all who dare to break “the Lore.”

This is a story about the hero who stands up for what he believes in.

Introduction by Jack Goodluck

In the 1970s, for the first time in Australia, a legislation was passed that provided for Aboriginal people to claim ownership of their traditional lands. This coincided with the transfer of mission stations and government settlements to the control of Aboriginal community councils.

This story is about people in the circumstances of that time of change. None of the characters represent any real person, alive or dead. The Wainandas and the Ananardus do not represent any real groups. Their lands are said to be in and near Western Arnhem Land, and therefore they do use some words from a common language of that area. Goose Island, N.T. exists only in this story, as does Malangarri, but nearby Croker Island and South Goulburn Island are real. Two ancient legends, about the moon and an ogre, and the historical stories of a sea monster and of the inter-clan massacres, are public domain stories given to the author while living in Arnhem Land.

None of the characters in positions of public leadership or service represent any real person, living or dead. But the range of attitudes and the kinds of circumstances that are represented here are common in the territory.

Small remnant groups of various clans had, before then, taken refuge on missions and settlements, and had adapted, during three generations, to the ways and laws of mission stations and government settlements. Now the settlement superintendents and most of the missionaries were gone, and the clan remnants were labouring with the enormous responsibility of living together and trying to govern according to foreign notions and foreign structures, such as a community, a town council and public ownership across the clans. Their situations were utterly different from what they had known under the Mission or Settlement regimes or on cattle stations, and were nothing like their own traditional ways of being a lawful and productive network of independent and autonomous nomadic clans.

There was a considerable movement back to ancestral homeland areas with modern facilities that they chose to have, and young Aboriginal adults were needed in those places to cope with modernisation and to teach and lead through modern dangers and confusions. Mani and Helen are fictitious characters, but there are many Territorians in their generation who would understand from experience the predicaments in which they find themselves.

This is about a few characters coping with life and with each other.

There has been a growing awareness that mutual trust between First Australians and would-be helpers is essential to any kind of recovery from present disastrous set-backs.

In his book The Politics of Suffering (Melbourne University Press, 2009) Professor Peter Sutton, a long-time fellow worker and student in remote communities, almost despairs of any relief from present sufferings in crumbling communities. Policymaking and interventions will not end destructive trends, and neither will popular liberation movements. The “Reconciliation” that Australia has to achieve is a personto-person thing, he says (page 209).

My story is about people trying to really relate to each other and to serve the needs of First Australians. Mutual trust, the essential element, is not easy to achieve, and without it the social break-down will continue.

I am a story-teller now, but for five years I conducted staff formation courses for community workers, trainers, jail-guards, adult educators and medical staff, as well as First Australians, at Nungalinya College in Darwin. The Commonwealth Government funded it all, including three month residentials.

We learnt together to be “trusted friendly helpers” to each other and to fringe dwellers of Darwin. Some of our students are still at work, forty-two years on, supporting community development. Sadly, there appears to be no similar staff recruitment and training today.

Jack Goodluck

Back On Country, is a term used by First Nations people that covers; having (their) land restored; life and connection to the land; with self-determination; recognition.